For the first time in Belgrade: “Besieged Sarajevo”

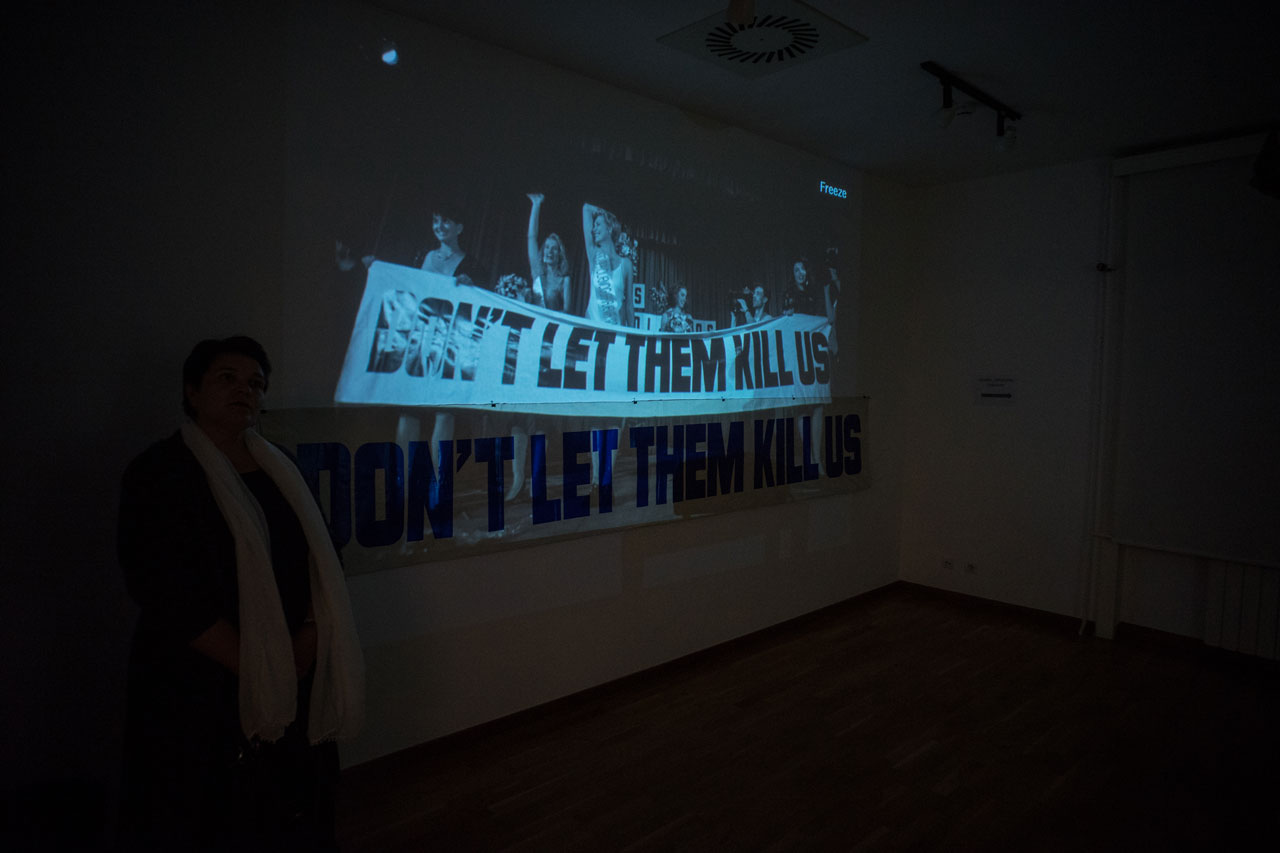

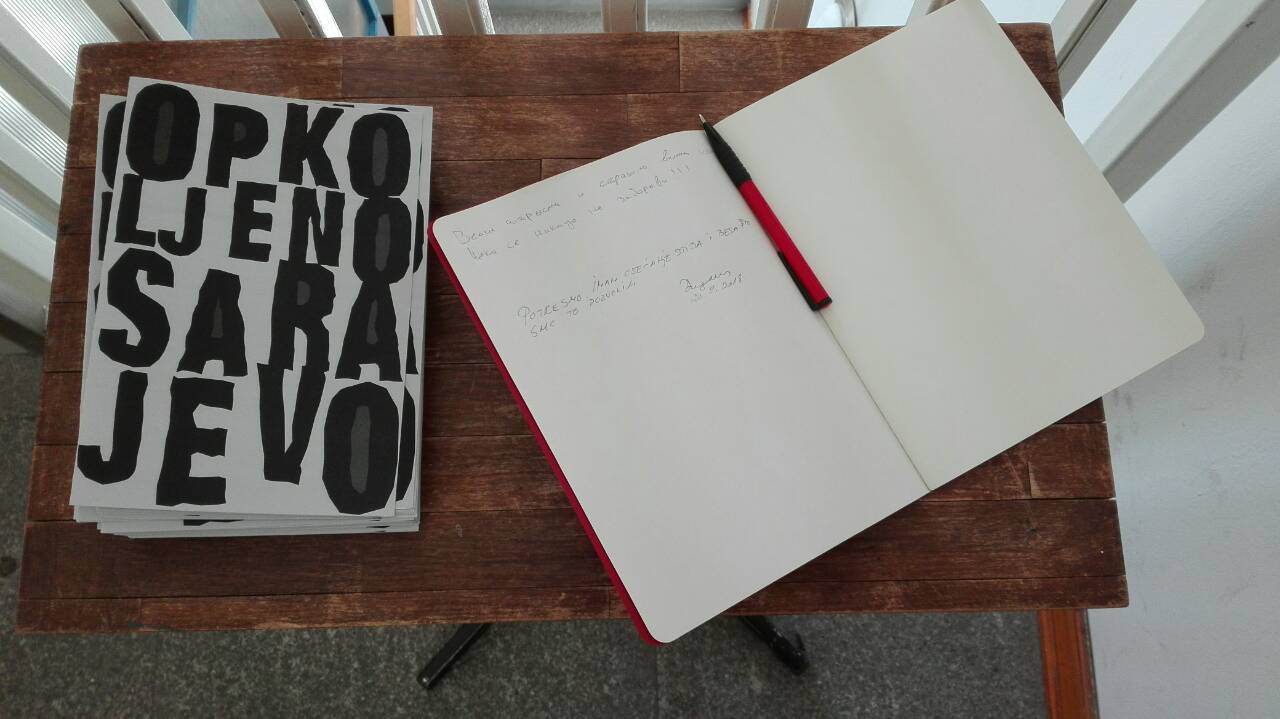

From September 25 to October 6, 2018, the Humanitarian Law Center (HLC) and the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina presented in Belgrade a part of the museum’s permanent exhibition, entitled “Besieged Sarajevo”. With photographs, documents, and hand-made items made by citizens of Sarajevo, the exhibition depicts life in the city that the Republika Srpska Army (RSA) kept under siege for 44 months. Visitors could see what life in a city without water, electricity and heating looked like, how schools operated, how children played, and how food was procured, along with other daily activities in the city that, despite everyday sniper attacks from the surrounding hills, sought to preserve the illusion of a normal life.

From September 25 to October 6, 2018, the Humanitarian Law Center (HLC) and the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina presented in Belgrade a part of the museum’s permanent exhibition, entitled “Besieged Sarajevo”. With photographs, documents, and hand-made items made by citizens of Sarajevo, the exhibition depicts life in the city that the Republika Srpska Army (RSA) kept under siege for 44 months. Visitors could see what life in a city without water, electricity and heating looked like, how schools operated, how children played, and how food was procured, along with other daily activities in the city that, despite everyday sniper attacks from the surrounding hills, sought to preserve the illusion of a normal life.

The exhibition in Serbia was presented in the context of growing tendencies to conceal or misrepresent events from the wars in the former Yugoslavia, especially after the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) ended its work in December 2017. According to a survey conducted that year, more than 70% of Serbian citizens did not know that Sarajevo was under siege during the war in BiH. The HLC has challenged these tendencies by organizing the exhibition, and educational and informative sessions and panels, as well as by involving young people in spreading knowledge and establishing cooperation.

About 50 citizens attended the public lecture on the Siege of Sarajevo held on September 27, with Nemanja Stjepanović as the lecturer. On that occasion, Stjepanović presented the facts which the ICTY determined in regard to the Siege of Sarajevo, indicating that the Sarajevans were the target of deliberate attacks by the VRS forces, mostly conducted during the daytime and not as responses to any military threats. The citizens were attacked while performing their everyday activities, such as driving on public transportation, or going to the store, school, playground or park, or at funerals. It was a widespread campaign of shelling and sniper attacks on Sarajevo, with the basic aim of spreading terror among the civilian population. For these crimes, the ICTY sentenced Stanislav Galić, the commander of the Sarajevo-Romanija Corps of the RSA, to life imprisonment, and Dragomir Milošević, his successor, to 29 years in prison.

The movie “The Siege”, by Remy Ourden, attracted considerable attention from the audience, so an additional projection was organized during the same period. Through the lens of this journalist, the movie depicts the sufferings of the civilians, and their creative ways of survival and attempts to preserve the illusion of “normal” life. After the movie, a conversation was held with the author, and Meris Mušanović, who as a young boy spent the entire siege of the city in Sarajevo. In his testimony, Meris said that the war permanently marked his family and forced him to grow up early. For him and his fellow citizens, the siege of Sarajevo represented the fight to remain part of civilization, since all modern-day achievements were taken away overnight: heating, water, electricity, education, medical services… For him, it was also a struggle to preserve the multiculturalism of this city, and build resistance to ethnic separations imposed on its inhabitants from the outside.

Meris tried to find refuge from the siege in books. His mother gave him an opportunity for that, letting him choose a book to read every seven days, after which the book would be burnt as fuel for heating. The abundance of books in the family library opened up new vistas for him, and led to his life-path and profession later on. From these books, he learned that the keys to overcoming difficult situations are a sense of responsibility and forgiveness.

On Friday, October 5, the latest book written by the Professor of International Law at the American University in Washington, Diane Orentlicher, “Some Kind of Justice – The ICTY’s Impact in Bosnia and Serbia”, was presented. On this occasion, the author presented her findings on the ICTY’s influence on local communities in the two countries, and how this influence changed over time. Alongside the author, the experts who used to monitor directly the processes before the ICTY, Erna Mačkić from the Balkan Research Network of BiH and Nemanja Stjepanović from the HLC, spoke at the discussion. Since this was a valuable opportunity to discuss this topic in the context of the influence of the ICTY on communities in Croatia and Kosovo, the HLC invited Hrvoje Klasić from the University of Zagreb and Kosovo journalist Adriatic Kelmendi to participate. They spoke about the crucial impact of politics on perceptions of who is to be considered a victim, as was the case in Kosovo during the parliamentary vote on the establishment of the Special Court, which was the first time that victims of other ethnic communities were mentioned in the Kosovo Parliament. They warned of the dangers posed by divisive ideas, instead of networking and community co-operation, as is the case with the insistence on the correction of the borders between Serbia and Kosovo, which creates an ever-widening inter-ethnic gap and sends a message that the different ethnicities cannot live together. They also pointed to the paradoxical situation in which the post-Yugoslav countries find themselves, as despite millions of pages of court files about the crimes committed and the responsibility for them of individuals and certain institutions, local societies do not know, or do not want to know, or pretend not to know what happened and to whom. Instead of striving for knowledge, they are raising questions about the nationality of the victims. They also mentioned the fact that the work of the ICTY has left a legacy of judicial rulings regarding war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in Srebrenica, which would have been difficult to achieve had these matters been left exclusively to the domestic judiciary. However, different ethnic communities accept these court-established facts in different ways, and the nature of their acceptance is determined by their perception of the prosecution of members of “their own people”. Since the ICTY has closed down, it is as if there is a perception in the society that there is no need to read the judgments and recall the established facts.

During the exhibition, an exchange programme was organised involving a total of 19 young people from Serbia and Sarajevo. Since most of them had never visited Belgrade or Sarajevo, and the programme allowed them to become familiar with the local way of life, the culture, and the history, and the manner in which these communities remember victims of the wars in the former Yugoslavia.